The Skagit

Reason to Believe

The Skagit river flows through me. The city of Anacortes pumps water out of the river into settling and treatment ponds. They then pump it about 15 miles to reservoirs scattered in the hills above the city. The utility serves some 60,000 accounts. When I turn on my faucet - it’s the Skagit.

The Skagit powers me. Two dams on the Baker River (tributary to the Skagit) provide hydropower to the cities and towns in Skagit County. Three more dams on the Skagit serve Seattle and its suburbs. When I turn on my lights, turbines whine as the Skagit spins electricity.

The Skagit feeds me. 90,000 acres of fertile bottomland irrigated by river water provides dairy, meat, and vegetables. Levees, dikes, dams, and drainage ditches control the flow of water across the fields and protects them from floods and seawater intrusion. Thousands of years of Skagit flood deposits made dark, rich soil perfect for agriculture. The salad I eat and the tulips I love grow in good Skagit dirt.

The Skagit inspires me. From its headwaters in the glaciated high country to its sand-barred mouth on the Salish Sea, the Skagit connects me with the other-than-human community. The Skagit shows me eagles, orcas, salmon, bears, marmots, deer, elk, cedar, spruce, and maple. The river is generous. It gives me icy high lakes and creeks, green meadows and glens, deep valleys, a muscular, fast, and flat mid-river glide, and a slow marshy release to the sea.

My thoughts are made of Skagit water, energy and inspiration. My thoughts are Skagit thoughts.

Two hundred years ago, the Skagit ran unfettered from the mountains to the sea. The river snaked across the delta in a million braided marshy channels before meeting the Salish Sea in an estuary near present-day LaConner. Millions of salmon and steelhead spawned in its gravelly banks. Salmon smolt moved from marsh to open water and back before going offshore. Hundreds of thousands of seabirds, geese, swans, and songbirds rested on their migration routes north and south. Eagles, bears, orcas, and cats ate their fill. The Coastal Salish people who lived along the estuary and river dug clams, harvested oysters, caught salmon, ate berries and fruit. They traveled up and down the myriad waterways in ornate canoes. They revered the river and had a deep connection to it. They were river people.

Today, wild salmon barely number in the thousands, and some endangered stocks only in the hundreds. Genetically inferior hatchery fish are released by the millions to compensate, but introduce disease, consume resources, attract predators and dilute the diversity of the wild population. Salmon populations continue to decline regardless of - perhaps because of - hatchery releases. Commercial salmon fishing has collapsed. People clash politically over ineffective salmon restoration efforts. The broad black mud marsh is gone, replaced by a narrow band of silty sand at the mouth of the river. The clams and oysters once found in Skagit and Padilla Bays are gone. The river is controlled by levees and throttled by dams. Habitat is lost to tree farms, stores, and development. Transportation is via screaming interstate highway or thundering rail line in lieu of canoe, schooner, and steamer.

We are not river people. Our connection and reverence lie elsewhere. To us, the Skagit is a manageable resource not a divine power and we manage it for maximum economic benefit. Farms in the delta grow everything from corn and potatoes to kale, arugula and tulips. Clean, fresh water hydrates one hundred-fifty thousand people - every day. Megawatts of electricity flow to millions. This is all good, sure - but it’s not a bargain. It costs us salmon, old growth forest, and sanity.

And the eternal Skagit rolls on…impervious.

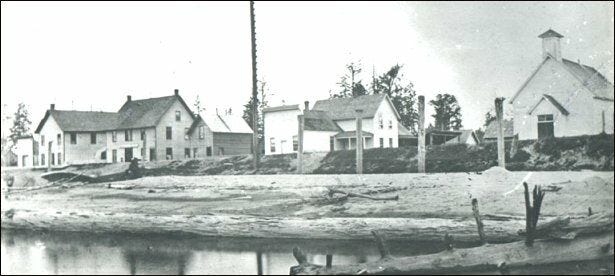

This morning, I walked along an overgrown wide flat bench on the river side of the levee. Here was the site of the first substantial town along the river settled in the 1870’s - Skagit City. Shallow draft steam ships would tie up to the shore here and offload goods and passengers on the wide beach. There were saloons, a church, a hotel, post office and a school. Today, a pile of trash lies in the rude parking area and of the town there is not a trace.

Later, I walked the slender remaining delta of the North Fork of the Skagit. The walk is about 9/10’s of a mile from a dead end road on a levee to a knob of granite called Craft Island. I strolled through the marsh and drying mud. A lone eagle in a tree on the island eyed me and the dog. Cat tails, queen anns lace, red-winged blackbirds, swallows and the smell of black muck reminded me of the wetlands on our family farm in New York. From the top of the island, I saw the sandbars of the delta extend a mile or more into the Salish Sea towards Whidbey Island. A slight breeze blew inland from the sea and the ebb tide raced south. It was quiet, still, holy - divine.

The Skagit is a magical river at the heart of a beautiful ecology. In the process of delivering snow-melt to the ocean it nourishes salmon, cedar, men and tulips. There is nothing more wonderful. It will flow long after our arrogant, broken culture is gone. It cares not about economic vitality. Yet, it will inspire and feed and transport the next culture and the one after that. And maybe, someday, humble river people will worship the Skagit again. The salmon, oysters, clams, and whales will return. The clamor and fury will cease. Gentle people will live in harmony along its banks and estuary.

I believe in river people. I believe in the Skagit.