Like fallen angels fleeing heaven, we abandoned Island in the Sky and dropped off the mesa into the canyon country below. Passed the two-mile, two-lane SUV traffic nightmare at the entrance to forsaken Arches, across the Colorado, and into schizophrenic little Moab, Utah.

On one blessed corner was Back of Beyond Books, a small outpost of sanity, stocked with the sacred words of the old desert prophets. We found original, signed copies of Edward Abbey's work, and a shelf just inside the front door crammed with radical and subversive environmental writers, including Lopez, Snyder, Peacock, Abbey, and Whitman. The place smelled like paper, ink, and quiet rebellion.

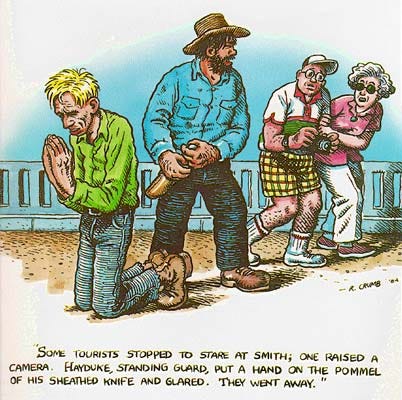

But cruising the main drag through town with our newly purchased bag-o-books, every other corner had a 4x4 vehicle rental place promising tourists a chance to rip and rend the backcountry, to defile what little still stands untouched. They sold rousing Disneyland adventures in the once pristine back country via roaring, infernal machinery to overweight, bougie Americans. Try not to roll the damn thing over like a beetle on its back...sir. They sell sacrilege.

Poetry, literature, and subversion on one corner. Rabid, aggressive economic plunder on all the other corners. Once, Moab was a quiet, ramshackle backwater hideout for desert rats. Now - at the risk of being labeled a grumpy old iconoclast - Moab is a touristy money sink. The decline started when new-fangled mountain bikers discovered slickrock in the eighties. It accelerated when Polaris, Razor, and Kubota created grown-up versions of Tonka toys that could crawl over house-sized boulders. Now, gearheads overrun Moab, bent on macho, industrial, motorized recreation. Moab is lost. The Chamber of Commerce is ecstatic. The desert bleeds

We fled south to escape Moab and camp in the Needles. We drove past the thousand-year-old warning ‘glyphs at Newspaper Rock and down into the snow and wind. We snagged a campsite just before a full-on blizzard erupted. Whiteout. We beat a hasty retreat back to town with our tails between our legs. The desert prevails.

Morning came, and the sun god blazed down on a new day. We didn’t wait. We hit the road early, hauled out of town toward Lee’s Ferry by way of Monument Valley, chasing silence, weather, and a place not yet ruined.

Monument Valley is a cathedral of stone and silence: no architects, just wind, water, and a few million years of erosion. Towers, buttes, mesas, and monoliths rise out of the desert floor, the bones of the spirit world.

As we drove south, the land swelled and opened, bare and brutal, stripped of all ornament except light and shadow. Incredible hulks of sandstone stood like sentinels guarding the secrets of deep time. They were not friendly. They did not welcome us. They tolerated us, so long as we didn’t stay too long or talk too much.

This is Navajo country. The land is lived in, not on—spoken to, sung about, and prayed over for centuries. The place hums with stories. You don’t need to understand them; listen. The wind translates. Here lies wild freedom, if you can handle it.

I took photos, hoping to capture the light when it slants just so, and the monuments glowed. But photographs can’t tell you how the silence tastes. Or how the red dust smells after a summer rain. Or how a raven looks when it hangs in the sky without moving a feather, watching you like it knows something you don’t—and never will.

Time quit. The ticking stopped. Monument Valley didn’t care who we were. It knew nothing of trucks, cameras, or humans. It was here before we were born, and it will be here after our bones are dust. Monument Valley is beyond time. Monument Valley is Earth. Monument Valley just is.

Spooked by monumental spirits, we were away to Lees Ferry, where the red rock meets a restless green river and silence. The place is a mix of loony history and raw geology: Mormon wagons, steamboat dreams, and a billion years of layered, vermilion cliffs. The Colorado churns nearby, not yet tamed by the brutal dam, still wild somehow. Here is rock and cactus, sand and silence, nothing more, nothing less.

We pitched our tents in a remote corner of the gravel campground, near the chalk-colored Paria River, and went exploring—a short hike along the Colorado to view the rusted machinery and old cabins of miners past. A longer hike up the Paria to view the old Mormon farmstead, sneak past the cemetery, and touch the gateway to the Vermillion Cliffs Wilderness. The Paria Canyon demands attention. We plodded on, sweating and grinning like lunatics, because this eternal Sun and these wind-chiseled stones were holy Mother Earth. We didn't hike to conquer, but to remember—an ancient, feral something that no dam or road, ranger station, or homestead can ever erase. We hiked to savor the gift of the desert, to know, taste, and sweat freedom. Ol’ unfettered Cactus Ed popped a beer here, sat by his fire, spat, and called it paradise.

At night, the stars wheeled and spun close enough to touch—no filter, no light pollution, Mars and Jupiter followed the Sun down. Infinity hung above, and the river whooshed below. The fire muttered, and our freeze-dried dinner tasted like burnt earth and freedom. I slept with dreams of John Wesley Powell paddling one-armed into the unknown maw of the Grand Canyon and marveled at his foolish bravery.

Up early the next morning, I had somehow lost a day and was now a day behind. The desert gleefully obliterates human notions of time. I hoped to dawdle across Southern Utah but now, we would have to haul ass. So, up and away to cross Utah and Nevada on our way to Bishop, California.

Big Red eased onto the ribbon of asphalt, grumbled his way up through Vermilion Cliffs and past Jacob Lake, and climbed and twisted up Cedar Breaks. There, high above the desert, the land became alpine. Creosote and ocotillo turned to pine and aspen. Two feet of snow still buried summer cabins. The air was thin and sharp, like juniper smoke. No tour buses, no gawking tourists—just wind and silence and the hum of stories older than roads.

Down off the Breaks, gas up in Cedar City, and cut northwest through the nothingness of Nevada. We camped for a night in Cathedral Gorge State Park near Panaca, Nevada. An otherworldly landscape of hoodoos and slot canyons, Cathedral Gorge is strange and spooky - Nevada at her best.

The road curled on into absurdity: the Extraterrestrial Highway. Twenty-five-mile stretches of heat-shimmered pavement vanished into floating blue mountains. Rusted mailboxes, conspiracy signs, and old abandoned motels/gas stations punctuated roadside vistas. There were no aliens, but plenty of ghosts—ranchers, miners, and maybe a few drifters who fell in love with the loneliness and never made it out.

We blew into Tonopah untethered as tumbleweeds. Tonopah teeters between the long, dry, hopeless Nevada desert and California’s promised land. Tonopah is neither. Drifters gather at gas stations hoping for work or a ride out of town - either will do. The mines are about played out and the casinos aint hittin’. Just fuel and groceries here now. Tonopah is drying up, soon to blow away. There is, though, the unnerving Clown Motel, where we did not stay.

Thirty miles south of Tonopah is the sho-nuff ghost town of Goldfield. Thirty million dollars' worth of gold bullion was extracted from the hills around Goldfield in the early 1900s. Hell, even Virgil and Wyatt Earp lived for a bit in Goldfield…trying to make it big in another rowdy town. Virgil died of pneumonia here in 1905.

The good people of Goldfield tirelessly ripped gold from the ground until there was none left. In 1906, the population was 25,000; by 1920, it had decreased to 4,000. The 2025 population - maybe 200. Tonopah and Goldfield - American boom towns, American tragedies, American omens.

Finally, we drove the last couple of hours from Tonopah to Bishop down the valley between the White Mountains on the left (east) and the Sierra on the right (west). New snow skiffed the Whites up high. The Sierras had old, deep snow in the draws and couloirs. The sky was an immense dome of brilliant blue.

Two days later, our trek ended in Vegas when I dropped Mike off at the Delta Airlines counter for his redeye flight back east. Two days after that, I had boomed back fast to Anacortes, only stopping once at a noisy trucker motel near Boise. Back home, under the long, grey cloud, surrounded by tall pines and maples, I curled up next to Dawn and dreamed of blue skies, red cliffs, and open roads.

REFLECTIONS

Three weeks in March. That's all the time this trip took. We went too fast, too far. Next time, we'll go further afield and stay longer, exploring more thoroughly. We needed to travel light and fast to fit everything in, see everything we wanted to see, and get just a taste of the great American Southwest.

Every trip has a big idea behind it. For this trip, the idea was a question. Was liberty and freedom implicit in the land of this country? Somehow, did the land itself contain the seeds of independence? Did our hunger for freedom come from the dirt we trod? Is freedom our birthright?

Yes is the answer. Once you glimpse the Vermillion Cliffs, or Zion Canyon, or Bryce hoodoos, or Island in the Sky, or Paria Canyon, or Monument Valley - they set loose a wild, free spirit. You are part of something grand, extreme, and beautiful.

It's the hush of wind over sandstone, and the spill of light across immense cliffs. It’s the space and clarity of 100-mile views. It’s the wheeling stars above. It’s the joy…the immense joy…bursting from you, same as a desert waterfall. It asks nothing and gives everything.

And in that moment, you are untethered, unafraid. The wildness you’d forgotten awakens. And you realize—gently, irrevocably—that you belong to something immense, fierce, and exquisite.

Peace.

We’re all just slow dancing in a burning room. Play us out, Johnny -